The Abdominal Wall and Attraction to Potential Partners

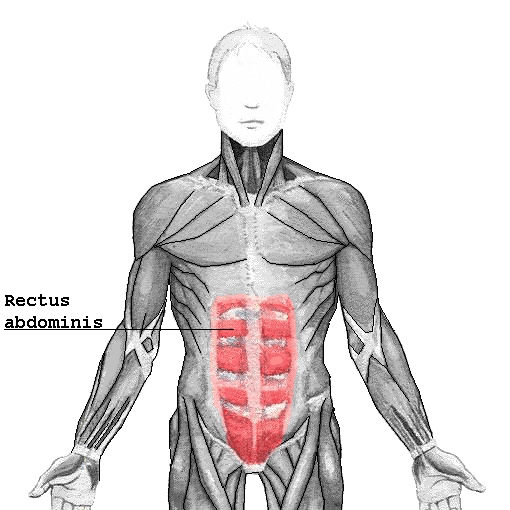

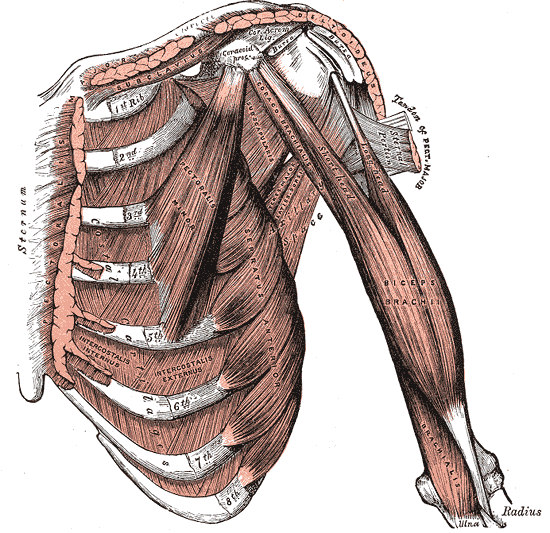

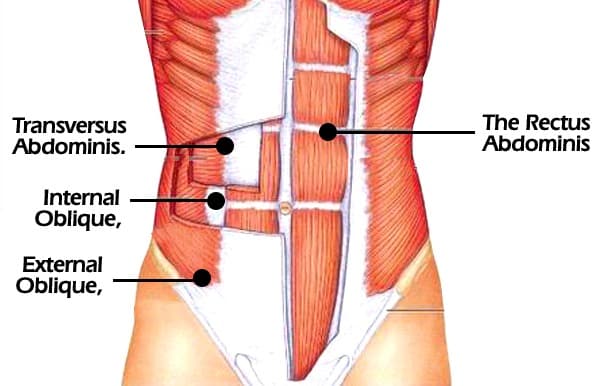

Have you ever been at the gym doing crunches and planks with your buddies and had no idea what you were doing? When you start talking about what you are working out, you are discussing abs, or abdominal exercises. Most often what we are talking about when working out or exercising is the rectus abdominis … Read more